Speaking to a great gathering of miners and estate workers, in 1875, at the

coming of age of his son George William Henry Vernon, August Henry Vernon,

the 6th Baron, referred to the work done by the colliery management, and

promoted by himself, in the field of improved conditions of ventilation and

safety in the mines, and in the provision and improvement of housing, and of

water supply. He went on,

"If people are entirely dependent upon the goodwill and good offices

of their landlord, and do nothing for themselves, they are reduced to a

state of dependence which I feel sure so independent a body as the colliers

of Poynton would at once reject. You have certain duties to perform in your

own houses ..... to keep them in order, not to have them too fully occupied

and to keep a general regulation over the conduct. As regards all works of

self-help out of your houses, I see strong evidence in this place of a

desire to foster habits of self-help by the Cooperative Society, the clubs

winch exist in this place, the Accident Society and so on; ..... One means

of self-help is by general cultivation; ..... I desire earnestly that you

shall as far as possible second the efforts ..... made in this place by

sending your children as regularly as circumstances will admit of, to the

... excellent schools in this place."

These remarks at a time just before the miners' unions became more powerfully organised on a regional and eventually a national basis, illustrate the strands of the story in this chapter and show the benevolent paternalism which existed at this time between the Vernon family and the Poynton community. This chapter first describes the more large scale activities deeply involving the managers of the collieries, and then those self-help activities promoted mainly by the miners and Poynton community themselves, namely the friendly societies, Cooperative Society and Working Mens' Club. The mining community gradually evolved independently minded leaders who were willing voluntarily to promote and serve their fellows, many of them imbued with the deep concern which was fostered by the strong Methodist movement; in which they also learned the skills of management and accountancy needed to run their associations. Many of the miners originally came from Methodist country in Staffordshire.

Miners' unions

The first union activities of miners at the Poynton Collieries occurred during the days when W.H. Fisher was Lord Vernon's agent. In 1833 miners in the area who had formed a union locally resisted cuts in wages and for a while miners were locked out at Poynton, and again in 1839 there was a strike resisting wage cuts. Men from many local collieries met in a field near the Horse Shoe Inn in High Lane following the stopping of four pits in Worth by Thomas Ashworth, now the agent, who said men were to be allowed back only after a wage cut needed because of a reduction in coal prices. Ashworth was alleged to be bringing in blackleg labour, and he alleged the miners were "abusing with violent language and other intimidations those who were willing to work." Tempers were high. This dispute became entangled with the Chartist movement which was promoting rebellion against low wages. During the period 1842-1847 this led to a Miners' Association in the North West with 100,000 members, fully described by Challinor and Ripley.1 The 5th Lord Vernon, when appealed to, had every confidence in his agent; he could not approve of threats to Ashworth's life and a pistol being fired in one man's bedroom (a blackleg or knobstick as they were called locally). Rioting took place and cavalry had to be brought in but by October 160 Staffordshire men were working without molestation. The union had caused Ashworth to restore the old wages helped by an improvement in the market which allowed the average wage of the district to be paid. Gradually Ashworth built up a more confident relationship aided by the genuine concern of a Quaker for the education, housing and welfare of the many "human souls" for whom he was responsible. In 1842 as part of the Plug riots, Staffordshire miners marching under Chartist banners came to disrupt factories and mines in Congleton, Macclesfield and Bollington. In July they reached Poynton which was protected in advance by the summoning during the night of soldiers of various groups, e.g. the Royal Dragoons. The 150 miners who reached Smithfield Pit off Coppice Road did not succeed in persuading the men to stop work as they were already being paid more than the invaders were demanding. They retreated in face of the military opposition. There were further strikes for several months at Poynton over the bond on terms of employment in which Ashworth was said to be including a promise not to join a union or strike. But in his first surviving report in 1845 Ashworth noted the increased prosperity of the collieries following the building of the colliery railway and claimed that the miners were more contented, more fully employed and better housed than ever.

In the 1840s the bigger colliery owners were able to resist and there remained great differences in conditions in different areas - the men being most inclined to support very local rather than regional or national associations. When Ashworth retired in 1858 after 25 years as colliery manager despite the stormy start to his administration, an impressive tribute was paid to him by 900 of the workers in the mines and on the estate - especially the better wages he paid and his concern for the social, moral and religious improvement of all classes. A fine calf bound volume was presented to him.2 Ashworth in reply comments on his increasing regard for the workforce and the industry with which, aided by Lord and Lady Vernon, they have created improved community institutions and showed their religious concern by attendance at Sabbath worship. Despite his lack of engineering knowledge Ashworth had created a tradition of a good caring relationship between employer and employee which meant Poynton miners were better off materially and socially than many other mining communities.

During the next era from the 1850s to 70s under the management of the first G.C. Greenwell, a well qualified mining engineer, the District Association of Miners at Ashton became the most important union activity. At its national conference in 1858 improvements such as no children under 12 to work, an 8% hour day, better trained managers, weekly wage payments and removal of abuses in weighing coal, were strongly supported. In July 1873 at a further Ashton district meeting of the various local lodges, the Norbury and Hazel Grove miners lodge proudly bore a new silk banner which cost£30. It showed a happy well clad stout eight hour day man contrasted with a depressed 12 hour day man. Greenwell's autobiography shows his dislike of the unions, but his close relationship with the men.

The union took up the case of poor pay of day wage men and horse drivers at Poynton. Lord Vernon returned from Switzerland, (where he lived because of poor health), and met a deputation, investigated and probably settled the matter by arbitration. The Stockport Advertiser published a long report of the union's 1874 conference at which the annual report was presented giving a very good picture of the district's objectives and interests. By this time it was affiliated to the Miners' National Association which had 146,000 members - though very few Poynton miners belonged to the latter. From the subscription of Is a week for miners and 9d for daywagemen a labour and checkweigh fund had been set up to secure control of weighing and improve pay and conditions, support men in dispute and "extend the principles of self-help in all other mining districts"; also a funeral fund for providing£6 on death to members and small allowances on the death of children; and thirdly a widows and orphans fund - 5s a week to a widow for life, Is for each of children up to the age of 12 - the aim being to keep them in a respectable manner away from the stigma of the Union Workhouse (see next chapter). It was hoped to give help in the case of old age, infirmity and accident also. In 1872 following the Mines Regulation Act, partly achieved by union representations, those collieries neglecting proper ventilation and safety precautions had to adopt measures already adopted at Poynton on the advice of Thomas Mattocks for long colliery underground manager to Greenwell and Lord Vernon.

By the 1880s Poynton wages became more and more linked to those of the Ashton district which had successfully promoted in 1881 the formation of the Lancashire and Cheshire Miners Federation along with eight other districts. The Ashton district was prominent at the National Conference of Miners in 1890 in forming the new Miners Federation and provided its own secretary Thomas Ashton to be the national secretary. From the 1890s Poynton miners formed their own Poynton Lodge within the District Association for the Poynton, Norbury and Hazel Grove miners and sent large deputations (700 with wives and friends in 1891) to the miners annual demonstration which were partly concerned with union business and partly with enjoying the seaside attractions of Southport. They were ready to come out on strike in support of colleagues, for example for 13 weeks in August 1893 in a national dispute over a 25% reduction in wages. The colliers "lounged moodily about the street or stuck to their firesides," and because the young Lodge was short of funds, strike pay was soon exhausted. The strike was eventually settled by the conciliation board as already explained.

The coalowners were also by this time organised into a Federation which started in 1892 when Lord Vernon joined through his membership of the local Lancashire and Cheshire Coal Owners Defence Association, which aimed at "the mutual support of its members" with "combined action in disputes ... and the regulation of wages and other matters." The subscription was 1d per employee, and when there were stoppages 6d per ton lost compared to normal production was to be paid to members. There was a national Mining Association from 1854 and various professional associations such as the Manchester Geological Society and the Federated Institute of Mining Engineers to which G.C. Greenwell and his son made notable contributions on aspects of management and safety.

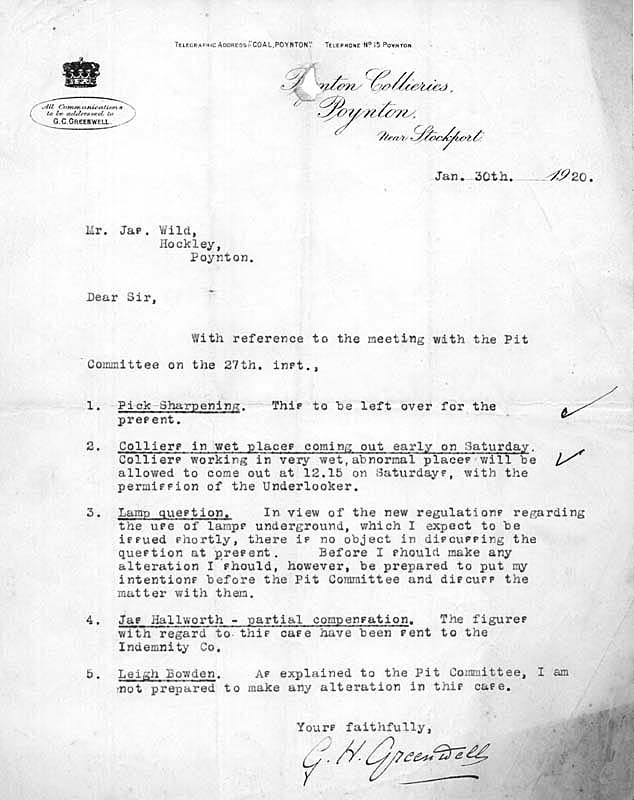

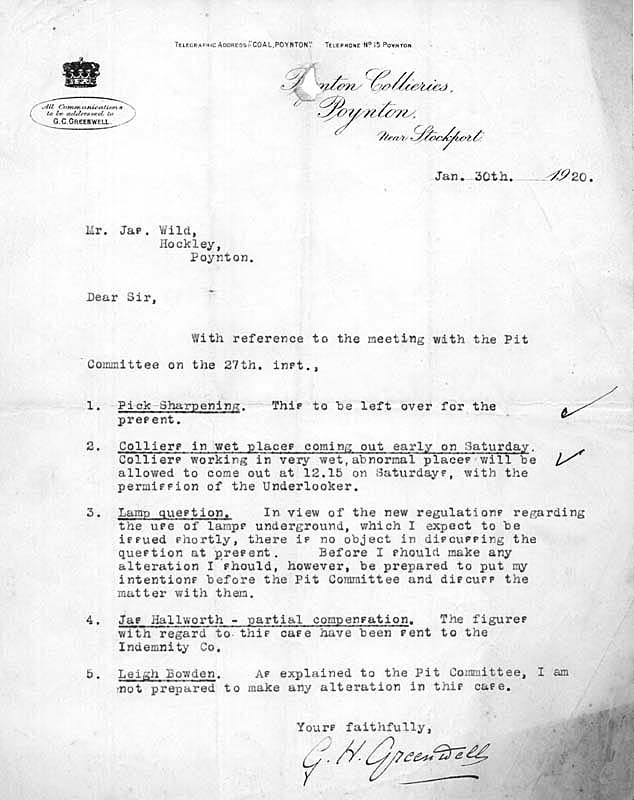

Besides achieving great advances in wages the Union achieved a general acceptance of an eight hour working day and encouraged the government to introduce successive regulations to improve safety and working practices. From 1904 until 1922 the monthly accounts of the Poynton Lodge have survived3 and illustrate in more detail the story of local union activities at a time when the collieries' own records are deficient. The income of the Lodge was derived from levies on members in the various pits varying from about 8d in 1904 to 1s 3d in the 1920s. A very interesting contributors book survives for the Anson Pit 1914-1921. Arranged in quarterly sections it lists the names of men in the various teams working at the coal face (103 in all), who paid 1s in 1914, boys and older men 6d - sometimes less when men did not do a full week. Then follow lists of the 36 daywagemen and 34 boys under 18. From the government figures of total workforce it appears there were 20 men who made no contributions - men who refused to join or who were elderly. The funds were invested with Blackburn Corporation (£1000 rising to £1,250 by 1905) and regular payments were made to the checkweighmen, who acted on behalf of the men, of £6 rising to £9 per week for each man at four different pits. £20-£30 was paid to the Accident Society and small payments to the officials, caretakers at Poynton (where the union met at the Baptist Church schoolroom) and Hazel Grove, also 5s to the man who cared for the Lodge's banner. This was taken over at the closure of the collieries in 1935 by the Park Lane Methodist Sunday School and is now preserved in the Poynton Industrial Archaeology Collection. The banner, despite alteration, still retains a picture of a miner receiving his wages with the text "the labourer is worthy of his hire." The Union also paid for printing copies of the current price lists and rule book.

At times of strikes, at severe cost to their balances, the Lodge with the

aid of funds from their parent union supported miners and their families. The

large national strike over wages in 1912 brought out over a million miners including

those at Poynton for four weeks. Details have already been given of this dispute

which resulted in much hardship. The accounts at Poynton show the depletion

of all the Lodge's invested money together with £571 received from the Federation,

leaving at the end a balance of only £80. £1,829 was paid in strike pay, an

average of 14s 6d per man for each of the 635 men. Gradually money was saved

afterwards and reinvested. By March 1920 after a period of hard work, good wages

and no disputes during the First World War, the union was expecting wage reductions,

because the mines were being returned to private ownership, and subscriptions

were raised to 1s 9d per man. The strike from 15 October to 19 November 1920

led to a payment of £2,500 to the men with the aid of £1,247 from the Union

leaving a balance of £42 at the end with £295 still invested in War Loan. The

next strike from 1 April until 8 July 1921 over further wage cuts resulted in

many people being without house coal, industry in great difficulties and the

Stockport gas supply only being rescued by the arrival of coal from America.

At the end the Lodge had only a balance of 9s 4d, all its funds, including investments,

together with £877 from the Union, £441 borrowed from the Accident Society and

£72 from the Benevolent Fund, having been exhausted.

|

|

Levies from the men had to cease and expenses were kept to a minimum, but after something like 11s per week had been paid out to each man for five weeks, there could be no payments for the remaining eight weeks of the strike and much hardship must have resulted. In the end the miners had to accept substantial cuts and the old system of basic rates fixed at district level, with percentage additions, returned. At the time that Poynton Pits were beginning to decline as coal became more difficult to get and the foreign market more competitive following Britain's return to the Gold Standard, came the General Strike of 1926 which lasted nine days. However the miners, for whom the T.U.C. had called the strike, continued to be locked out for a further seven months. Miner's families were in great difficulty, they had, for instance, to scour the dirt rucks and dredge the canal to retrieve many a ton of coal for domestic use, see earlier picture. In the end they drifted back, though many never got jobs again. Until 1935 all negotiations were conducted at national level, the local unions For the moment having no negotiating rights. Poynton men resumed work after 17 weeks out on reduced wages, Lord Vernon having stated that the pits would otherwise close because of high recurring costs especially for pumping water. When the pits closed finally in 1935 after a period of some success following electrification, union activity ceased except for negotiations over alternative employment.

The union assisted its members and their wives, except during the war and at times of strikes to enjoy an annual trip, often to Blackpool. Fares were paid to the L.N.W.R. and small allowances to each man, e.g. in 1905, 570 men each received 7s. Members were also protected by the union's attendance at inquests after fatal accidents; they also arranged for pit inspections so as to obtain adjusted rates for abnormal conditions; they helped in cases of illness and hardship and were generous in assistance given to hospitals, and the National Library for the Blind, to men who were on strike in other pits, and Belgian refugees in 1915. There is no doubt that the Union secured many benefits for the men, especially between 1890 and 1919, although there were always some who did not belong latterly when the Union became weaker.

Safety and the Accident Society

Coal mining is a hazardous occupation because of the underground location of the work which brings perils of roof collapse, explosive gas, flooding, the projection of rock in narrow passages and cramped conditions of work; poor light, heat, lack of ventilation and damp; and the movement of wagons, tubs, locomotives, heavy tools, cages, jigs and ropes. From the 1850s the central government was brought regularly into mining by the introduction of District Inspectors who were experienced engineers concerned chiefly with the prevention of accidents and the improvement of working conditions. This was a result of the horrific revelations of, for example, the Children's Employment Commission report on the mines in 1841. By 1855 an Act for the first time required general rules to be enforced in all collieries and special rules particular to each, many of which were concerned with safety and better working conditions. In 1862 single shaft operations became illegal following the Hartley Pit disaster, and, in 1872 and 1887, further Acts tightened up regulations with regard to safety, ventilation, conditions for shot firing and ambulance provision. The views of miners themselves had to be more and more taken into account. By 1882 there were five miners who were M.Ps. The accident rate per 100,000 men annually was reduced from 357 in 1867 to 113 in 1924.

At Poynton as elsewhere there were large numbers of men killed and injured in the early days, e.g. 34 between 1834 and 1849. No regular record was kept; but in 1848/9 there were 68 accidents, in 1852, 128 were injured and two died. Many hair raising escapes have been told to us by former miners who were interviewed, and there were minor injuries all the time e.g. one man described the "knapters" or bumps on the spinal column caused by constant abrasions of the skin in low roofed passages. The following table gives some idea of the types of the more serious accidents recorded in the colliery reports and the Stockport Advertiser between 1851 and 1897. Many of these injuries involved young boys, perhaps because of their inexperience. Firedamp was not a serious problem at Poynton but there were explosions at the German, Nelson and Oval Pits, and checks were made every morning before work began by the fireman or underground manager.

| Cause | No. of injured | No. of fatalities |

| Roof falls, falls of coal or bricks down shaft. | 15 | 9 |

| Run over or injured by moving wagons or tubs. | 14 | 8 |

| Explosions of fire damp. | 4 | 6 |

| Falls into sump, from bridge or from coal carts. | 3 | 0 |

| Cage - breakage of rope or crushing. | 3 | 1 |

| Blasting or inspecting charges which had not exploded. | 3 | 0 |

| Hit by bucket. | 3 | 0 |

| Entanglement with wires, chains or ropes. | 1 | 0 |

| Injured when oiling moving machinery. | 1 | 0 |

| Injured when repairing shaft. | 1 | 0 |

Total | 18 (66.7%) | 24 (33.3%) |

An example of the terrible accidents which occurred, apart from those already described in Chapter 9, happened in 1858 when three married men with children were killed in an explosion of firedamp at Park Oval Pit when they were searching for some missing wedges, used to support the roof, with a naked lamp contrary to instructions.

The first improvement in safety was the invention of the safety lamp by Davy

in the 1820s. Candles were certainly used at Poynton at first but safety lamps

were then adopted of various types and by 1892, 1,000 were used in the pits,

chiefly of the Howat Deflector type, some being serviced whilst others were

in use. A hand machine was used for screwing and unscrewing the parts of the

lamp, and for extracting and inserting the lead rivets with which it was "locked".

Unfortunately these lamps gave only a poor light which led to the common eye

disease nystagmus. This caused inability to focus and made some men unfit for

work. Another serious health hazard for which little remedy was found before

1935, was the dust in the air which affected respiration. Many miners had short

working lives and ill health or retirement because of asthma and bronchitis.

A notice dated 1853 has been preserved which illustrates the main hazards.

|

|

Besides the improvements insisted upon by government regulations, there was from the 1850s a voluntary Accidents Society4 actively promoted by Thomas Ashworth, who commended it in his farewell speech, and Lord Vernon, who paid an annual contribution e.g. of £10 in 1870, and supported by subscriptions from the miners. These subscriptions were deducted from wages at source. In 1852 this paid out £328 in relief from a fund collected of £354, and in 1857 £407 was spent on relief and medicine for 229 injured miners; i.e. in one year over 1/5th of those employed were injured. In 1873 Lord Vernon and G.C. Greenwell succeeded in securing the appointment of a well qualified doctor to serve the Society's needs, though at first the miners wanted someone else.

Some instances of the enforcement of government regulations through the courts are given, e.g. men prosecuted in 1875 and 1877 for leaving a winding engine in charge of an unqualified boy, and unlocking a lamp. In 1881 the Employer's Liability Act was passed, against opposition from colliery owners, making employers responsible for compensation to workmen injured or killed through the negligence of management. An attempt at Poynton by Lord Vernon to contract out and set up his own insurance scheme failed as miners refused, acting on union advice. To meet his obligations under the Act, Lord Vernon formed an insurance fund with the Provident Clerks and General Insurance Company, which offered men £100 death from accident benefit and 10s per week disablement benefit for up to three months at a cost to Lord Vernon of 3d per man per week. Very few claims seem to have been made on this fund. A later Act in 1897 was expected to be more burdensome; its local effect is not known but its cost by 1925 was reckoned to be adding 3d to the cost of a ton of coal nationally.

From 1890 it is possible to see more clearly how the Accident Society worked to help those where management did not have a liability to pay compensation. The main accounts show the amounts received in contributions related to men's wages, e.g. 10d per man per month for 568 members in 1907 plus 5d per man from 30 members who were sick. When a considerable balance accrued, this was invested, e.g. in 1915 £250 was invested with Barrow-in-Furness Corporation and in 1916, £97 in War Loan. Membership remained about 500-550 up to 1923. There was a regular payment of Is per member to Dr. Wise for attendance on those sick and injured but from 1913 payment to him was made of 1s 6d per member actually treated; 3s by 1921. There were also small payments to the Society's officers and generous payments made to the voluntary hospitals such as Stockport Infirmary £20; Manchester Eye Hospital, St. Mary's, Manchester £5, to which the seriously injured or difficult cases were sent and the Devonshire Hospital, Buxton £4 (cases of arthritis and rheumatism). Gifts and presentations were made to the Vernon family, e.g. £30 for the coming of age in 1909 and other notable people, e.g. £29 for a canteen of cutlery to R. Percy, colliery manager in 1919.

The most interesting features of the records are the details of payments made and the lengths of disability which sometimes ended in a funeral payment, e.g. James Marsland from his accident in 1891 until his funeral in 1914. If the year 1911 is chosen as an example, of the 97 cases of accident who received payment of 8s in the first week, 38 were paid for one week, 28 for two, four for three, eight for four, two for five, five for six, three for seven, three for eight, two for ten, two for 12, one for 13 and one for 33 weeks, while eight men's families received a funeral allowance of £ 5, out of a total membership of 580. Thus over 18% of the members received some payment in that year and there seem to have been payments to from 13 to 18% of members in the period from 1891 to 1913, and probably similar figures later. In 1915 of the 103 cases, 24 were treated by Dr. Wise, but by 1926 he was treating only one, two or three. In 1911 the numbers of new cases per month averaged nine and just over six continued to receive benefit after the first month. The illustration shows an actual month's payments. At any one time in 1911 some 15 to 16 cases were receiving payment. Sometimes lump sums were paid to help widows or the child of an injured man at a time of special need. The funeral allowance was increased to £7 10s by the 1920s. Payments were reduced after a certain length of time, varying with circumstances, such as whether a man was married or not. In 1908 payments came down to 2s only, after the first 15 weeks.

The work of this society continued in parallel with the work of the Friendly Societies described later and with sick benefits available under the governmental Insurance Scheme of 1911 for which contributions had to be deducted by employers from workmen's wages.

Pithead baths were never provided at Poynton though there was a proposal to use the £400 left to the workmen of Poynton by Fanny Lawrance, wife of the 7th Lord Vernon, for slipper and plunge baths and showers, but the cost proved too high and the money was eventually used to provide a working men's club. Some of the men interviewed mentioned the colliery ambulance station at Towers Yard building still there, (see plan in Chapter 10.) where a pony and trap with solid rubber tyres was always stationed in the 1920s to take injured men to the colliery doctor or Stockport Infirmary. First aid kits were provided at the largest pits from at least 1888 and extra safety was provided at the new Lawrance Pit in 1889 in the form of two Hepplewhite-Gray deputy safety lamps5 for the use of the firemen (see illustration). These offered a safer and more efficient way for them to test for gas. No doubt after electrification in 1927, the improvement in lighting reduced a little the dangers of nystagmus, though electric lighting was only introduced in the neighbourhood of the shafts.

When the pits closed the Area Inspector of Mines insisted on all shafts being fenced around to prevent accidents. Many were filled but Lower Vernon, Park Oval, Round and Lawrance shafts were still merely fenced and unseated until 1982 when the National Coal Board capped the latter three. Our long report includes a full list of all people killed and injured with the causes of accidents, where known, up to 1935.

Industrial housing

From a few hundred in the 1810s and 20s the colliery workforce expanded

to over a 1,000 in the late 1840s as the output of coal increased (see the graph

in Chapter 10.). From the censuses the number of houses is shown to be as follows

In relation to the population of Poynton, Worth being very similar:

| Population | Houses | No. per house | |

| 1801 | 432 | 75 | 5.76 |

| 1831 | 747 | 111 | 6.73 |

| 1841 | 854 | 149 | 5.73 |

| 1851 | 1247 | 223 | 5.59 |

| 1861 | 1284 | 258 | 4.98 |

| 1881* | 2166 | 431 | 5.03 |

| 1901* | 2544 | 534 | 4.76 |

| 1931* | 3944 | 1116 | 3.53 |

| * including Worth |

Thus the worst overcrowding was in the 1830s and 40s and the colliery owners became much concerned to improve conditions, especially as this was also the era of riots and strikes. In the earliest period of mining the small groups of miners lived in bothies or farm buildings near to the pits which were then mostly on the higher ground near to where the coal outcropped. In the 1790s large scale commercial mining began to be carried out and required a much larger labour force for pits which might well last ten or twenty years. Miners began to come in daily long distances from neighbouring townships or migrate from existing colliery areas in Staffordshire and Lancashire - taking whatever improvised quarters could be found in farm buildings, e.g. the former Poynton Corn Mill or living as lodgers. Small groups of cottages were built near to the deeper pits operated by steam power, such as the group called Accommodation at the top of Dickens Lane, and three surviving cottages at Smithfield on Coppice Road, listed in an inventory of colliery property of 1826.

In 1815 the Bulkeleys decided to assist the lessees of the colliery mining

rights, Wright and Clayton, by erecting in Worth Clough near to pits such as

Quarry, Clough and Anson, the large block of cottages now known as Worth Clough.

These are often described as Petre Bank, or Pear Tree Bank, the name of the

large sandbanks behind them which were removed in the late nineteenth century.

Originally there were 12 cottages plus a double one at the centre used as a

grocer's shop with a store on the first floor. They were built with solid brick

wails, nine inches thick and a stone slate roof and offered simple but adequate

accommodation of two rooms downstairs and two up, with sanitation provided by

an outside privy or earth closet at the back, separate from the house. Under

the stairs was a storeroom. The windows, one for each room, were originally

small paned and slid sideways, being of the type known as Yorkshire (an example

still exists in an old cottage in the Coppice). The front room was 15' square

and the rear 8'. Each had a good sized plot of land, mostly in front, through

which the brook ran, so that fresh fruit and vegetables could be cultivated

as well as flowers, and livestock kept. In the 1851 census most of the inhabitants

were miners, 63 in the then 13 cottages, one of the largest families being John

Lloyd, a miner, aged 57, his wife, a son 21 also a miner, three daughters, and

a lodger (57), also a miner. In another household there were nine, including

a grandson and four granddaughters. These cottages, because of their character

and historical associations, were placed in a General Improvement Area by Macclesfield

Rural District Council and restored in the early 1970s, some remaining in Council

ownership, others being privately owned. Damp-proofing and bathrooms were put

in for the first time and extensive repairs and landscaping were carried out.

A plaque on the centre cottage commemorates this work which fortunately preserves

an important part of Poynton's heritage.

|

|

| Worth Clough Cottages, Petre Bank c1900. Note original stone slate roof and sand bank behind. |

In the late 1830s several other blocks were built. An interesting example is

at Dalehousefold, (still to be seen off Towers Road), where the original (eighteenth

century?) stone farmhouse had all its farm buildings and much of its land taken

away for conversion by 1849 and ten cottages were added in a row extending the

farmhouse, with the usual gardens in front, separated by a paved road and coalhouses,

privies etc. at the rear. An example of squalid and overcrowded conditions was

described in the Children's Employment Commission investigation in 1841 - the

cottage in question being near the junction of London Road South and Park Lane

in a block pulled down by 1900 and roughly where the National Westminster Bank

is now:-

"Joseph Eccles, aged 54:-

With a wife and eight children, live in a home at Povnton-place, belonging to

Mr. Armstrong, having two rooms above and two below, each about ten feet square,

without garden; rent 2s 9d per week, and rates and taxes paid by the want. The

interior of this house forms a striking contrast with the four others, in furniture

and cleanliness. On entering the house we observed the wife, an old woman, clothed

in ragged and dirty apparel; the floor did not appear to have been washed for

a long tune, and the ashes were strewn almost to the middle and an old wooden

frame with a piece of sack thrown over it; up-stairs were three beds, very old

and very dirty."

Some cottages were built near the outlying farms, e.g. six at Pool House Farm and four near the canal wharf at Mount Vernon.

By 1840 the Stockport Advertiser noted that 70 houses had recently been erected in Poynton, some by Lord Vernon, to rent, others by the private initiative of individuals. Two examples of the latter are given in the 1841 investigation, namely the cottages of John Ridgway and Isaac Mottershead, (still there and numbered 260 and 258 Park Lane). Ridgway had saved up and built the cottage at a cost of £80 on land provided, at a chief rent, by Lord Vernon - "consisting of two rooms above and two below; very clean and well whitewashed the main rooms being 14' square with a ceiling height of 7'6"." There was a very large garden of 393 sq. yards and a croft for animals of 1270 sq. yards. Further cottages were added later at either end and the land redivided but the original cottages are still there. At this time the cottages at the corner of Poynton Green and Park Lane were built with their distinctive wedge shaped stone lintels and sills, but the major effort of Lord Vernon dated from 1844 when the block of 25 terraced houses known as the Long Row was built with local bricks and slate roof. The rooms on ground and first floors are shown in the plan made at the time. These cottages also were renovated by the Macclesfield Borough Council in the late 1970s, when the original character was preserved by the use of sash windows and doors similar to the originals. The cottages had pleasant large gardens at the front stretching across the brook, but now reduced in size. There was a tunnel giving access to the rear which caused a much smaller cottage at the centre. In 1851, 18 coalminers lived there as heads of household with many sons also miners (one had five) three widows, a railway platelayer and a carter at the coalmine, 130 people in all, just over five per house; many were young families who had only just moved in. The rents in 1849 were £5 17s per annum. Other blocks built by 1849 were Eight Row, on what is now Chester Road, near church, demolished in 1900 to make way for superior property; Ten Row, off Park Lane, (now with the recreation ground at its rear), which like Dalehousefold had pleasant plots stretching over the stream and houses which have now been modernised privately.

There still remained problems of men having to walk long distances from neighbouring townships, (less than half the workforce lived in Poynton in mid century); Thomas Ashworth and his colliery manager John Evans constantly urged the building of new cottages as a sound investment as they believed the coal would last for 100 years. There was by 1851, a builder, Peter Clayton at Midway employing 25 men, and brickworks near the present station, could by 1874 produce over a million bricks a year. G.C. Greenwell took up Ashworth's plea in the next major effort of colliery housing at Coppice Road when, using stone from the nearby Hig Lane quarry, four blocks of 8, 8, 8 and 10 cottages were built in 1873/4 with roads between them and behind, again having extensive gardens at the rear and pleasant stone porches and walled cottage gardens at the front. These had a front room, kitchen, scullery with two or three bedrooms above, and a substantial privy, coalshed and store behind and were collectively known as Newtown. There was some variation in the size of different cottages. The average rent was 2s 10d per week with an addition of 3s per year because of the large plots behind. The site was near to an important road intersection and at a point where a new water supply could be provided, as described in Chapter 7. Problems arose over subsidence from mining the two foot seam from Quarry Pit in the early 1900s and these cottages had to be supported with metal ties, some of which still pass through the bedrooms just above floor level, and pieces of metal or blocks of wood, (as shown on the photograph), from the colliery scrapheap. Giving evidence to the 1871 Commission6 which investigated coalmining, G.C. Greenwell said,

"we do not leave coal under buildings; we work out under them .... the

less important houses crack and then we keep mending them until the coal is

worked away, (the seams were mostly not very thick), and then they gradually

settle down .... some repairs have to be done but we do not make the houses

uninhabitable."

|

|

| Newtown Houses in Coppice Road c1900. Note reinforcement against subsidence. |

He mentions the higgledy piggledy shape of farmhouses, added to until they assume fantastic shapes, making repairs difficult. Lord Vernon, in his 1875 speech, showed he was well aware of the deficiencies of colliery houses. A policy of gradual improvement was followed. The maximum number of cottages available was 202 in 1881 when the total colliery workforce was about 600, so they played a substantial part in housing. The following figures for a sample year, 1885, give the receipts and maintenance expenses:- there were 201 cottages, 173 tenanted by miners, 22 by other estate workers and six untenanted. At an average rent of 2s 3d per week, £986 was received and £371 was spent on repairs, including £203 on labour and £169 on materials. £117 went on rates and taxes leaving a balance of £498. In some years well over £600 was spent on repairs, and whilst new cottages were erected, older ones were condemned and pulled down. Further building continued by miners from their own savings, e.g. in middle Park Lane at this time. In 1891 came the last colliery promoted housing effort when £4274 was spent on 25 new cottages which consisted of two blocks of six called Green Terrace on the south side of Park Lane just past Bulkeley Road, and blocks of six and seven on the west side of London Road North, not far from the coalyard, called Lyme Terrace and Park Terrace. Colliery bricks were used. All were the most substantial yet built, with sash windows, elegant doors with fanlights and marked with circular terracotta date plaques. They had very small front gardens and smaller plots and backyards behind, and contained sitting rooms, kitchen, scullery and three bedrooms. There was a new Post Office attached as an extra room, at the north end of Lyme Terrace and a larger house for the Clerk to the Colliery with bathroom and w.c. Rents varied from 2s to 3s 7d for the cottages, 4s 7d for the house.

By this time the very primitive sanitary arrangements were being criticised by the Macclesfield Rural Sanitary Board, which had been set up under the 1872 Public Health Act and became alarmed at the heavy outbreaks of diseases such as scarlet fever and diptheria which caused many deaths amongst children, to which bad water and poor sanitation were thought to contribute. G.C. Greenwell had been summoned in 1894 to answer complaints that sewerage from the village was being discharged into Poynton Brook from sewers laid by Lord Vernon. Improvements were attempted but when rates also went up after the formation of the Macclesfield Rural District Council in 1894, Lord Vernon indicated that the very expensive construction of a new sewerage system for the whole of Poynton, could not be carried out by him. In fact a special committee was formed by the R.D.C.,7 and by 1899 the new outfall works by Norbury Brook, below Chester Road, were completed and new sewers for most of Poynton connected up. This sufficed with increasing difficulties until 1937, when arrangements were made to send Poynton's sewerage into the vast Manchester system based at Davyhulme.

From the 1890s there was much private building along Park Lane, e.g. six houses were built in 1895 by Mr. Platt, a Crewe contractor, and six by the Coop in 1887, (see plaque), and elsewhere to accommodate a large increase in population - plus 600 between 1891 and 1901. After the sale of the Vernon estate in 1920, the catalogue for which provides a valuable record of all the Vernon's property and buildings on which they claimed the chief rents, the onus for providing housing for working folk passed to the R.D.C., who built houses in the early 1920s along Coppice Road, numbers 131 to 205, with good sized gardens, and in the late 1920s in the Dickens Lane and Vernon Road area, extending to Copperfield Road in the 1940s and early 1950s. Much more private building also took place as Poynton became a commuter suburb.

On the whole the housing story in Poynton compares favourably with the miserable accommodation that still persisted even in the 1920s when R.A. Scott-James8 reported very bad conditions in Durham, South Wales and Scotland, where e.g. in Lanarkshire in 1924 there were "rows of low cottages, some of them with two rooms, some one; with no pantry; coal is kept under the bed. Conspicuously huddled together in the yards are huts for sanitary purposes." In was in these situations that miners had acquired the reputation for brutality and dirty habits. Poynton miners enjoyed much better houses, plenty of gardens, rural surroundings, free coal and cheap gas and water.

Friendly Societies

There were several other organisations which Lord Vernon referred to in his remarks in 1875 as examples of self-help. Those now to be discussed arose mainly from the efforts of the Poynton community, promoted very much by the miners to overcome their risks and improve their standard of living, and falling very much into the Methodist concept of sober independence and thrift, Working men, and especially miners, were very anxious, both in the unstable period from the 1830s to 50s, and also in the more prosperous period which followed, to protect themselves from the risks of accident, ill health and the problem of leaving widows and children unsupported if they themselves were fatally injured. Poynton was in the area of the north west where both the greatest friendly society, the Manchester Unity of Oddfellows was founded in 1810, and the cooperative retail and wholesale movement started in Rochdale in 1841.

The earliest phase in Poynton revealed in the investigations of the Children's Employment Commission in 1841, was the formation of small local sick and burial societies, which for small contributions per week, paid members a small allowance during sickness and a funeral better than the disgrace of a pauper's burial - all that was available through the state poor law. An example was the Poynton Green Sick Society, to which miners belonged, paying Is per month and receiving 7s per week benefit, about 1/3 their average wage. The Commissioners criticised those who were in debt, prone to drink and improvidence. Probably many more miners belonged to the Manchester Unity of Oddfellows which by 1838 had 1200 Lodges, mostly in Lancashire and Cheshire, with 90,000 members. Five miners paid is 8d per month and received 10s per week. Thus out of the 14 mentioned by the commission, over half belonged to a friendly society. The Lodge in Poynton, founded about 1830 at the time the collieries were expanding, was known as the Loyal Vernon, No. 413. By 1845 it had 60 members and met at the Griffin Inn, (later the Vernon Arms), on the first Saturday of the month. It was part of the Marple District of the Manchester Unity, which had 885 members. By 1873 the Lodge had over 60 members still. In 1879 it published its general rules in line with government control of friendly societies, stating its objectives as "insuring sums of money for the burial of deceased members and their wives, rendering assistance to members when sick, assisting members travelling in search of employment and granting temporary relief to members in distressed circumstances?' There are listed very detailed arrangements about raising subscriptions, appointment of officers, administration and monthly contributions which varied from is 4d for the youngest age allowed, 18, to 2s 7d at age 44 with weekly benefits of 10s for six months then 5s for six months and thereafter 2s 6d, £10 at death of members, £8 at death of wife plus £5 from the District General Fund. Similar benefits and subscriptions were paid in 1928 from age 16. Benefits ceased at age 70. It was important to recruit new members in order to meet the needs of the more elderly who more often claimed benefit. The membership book from 1863 to 1920 shows an average of 4% members joining each year - more in some years, the most being 12 in 1892 and 21 in 1912, (at times of strikes and distress). There had to be strict control of sick visiting to ensure no malingering and Summer treats were arranged for the benefit of the members.

By 1891, when the mining community was much wealthier through higher wages, the Lodge had 120 members, while the whole Unity had 673,073, with a capital of nearly £8 million. It published Oddfellows' Magazine from 1828.9 Summer processions were held in the 1890s with full regalia, including the banner. Following is a description from the Stockport Advertiser in August 1894 of the anniversary of the Loyal Vernon Lodge-

"There was a muster of about 120 members, at the headquarters, the Vernon Arms. Headed by the excellent village band, the members walked through the village, and returning attended a short service held by the Rev. T. Bridges, who delivered an appropriate address. Leaving the church the procession was continued through the other parts of the village up Park Lane, by Newtown, Ward's End, Dickens Lane to the Vernon Arms, where a capital dinner was provided. Bro. J. Hallam was called to preside, Mr. H. Peover was the pianist, and Mr. H. Knibbs, harpist. After a loyal toast and toasts to the Manchester Unity, Marple District and Vernon Lodge the secretary responded, showing that the gain for the past eight months had been £49 8s 10 1/2d. Nine new members had been admitted and one death had taken place .... Songs, recitations, banjo and harp selections varied the programme."

The Lodge contributed to hospital funds and other charities. No doubt members derived great social value from this companionship. Up to the 1930s membership increased - maximum number being 245 in 1924 - of an average age of 41, with a recruitment each year of three to seven new members. The fall in wages in the 1920s and the unsuccessful strikes hit membership but at times of distress funds were collected from the richer lodges and distributed to those in financial difficulty. With the advent of state pensions in 1912, and sick benefits, the societies were involved in the government health insurance schemes as agents; the Poynton Sick and Burial Society being too small for approval under the Act, threw in its lot with the flourishing Poynton and Worth Cooperative Society's part in the C.W.S. Health Insurance Section which had 230,000 members by 1918. The minute books show, as well as sickness, state disablement and maternity benefits being paid, and by 1936, dental, optical, hospital and appliance benefits also. The Loyal Vernon Lodge still continues but with only about 30 members, mainly elderly. The National Health Service and other services have now taken over.

Other friendly societies serving the same purpose and having branches in Poynton included the Independent Order of Rechabites, founded in Salford in 1835, which compelled members to take a pledge of abstinence and was connected with the Methodist Temperance Movement. The Poynton branch, being called the Perseverance Tent, met in the United Methodist Sunday School for addresses, entertainment and tea parties. In 1828 a Philanthropic Society had been founded, which by 1886 had 150 members and flourished financially being able to pay out in 1892, 18s for sickness per week and £18 for funerals. They too had dinners and processions. Small numbers of miners also belonged to the Ancient Order of Foresters and the Loyal Order of Ancient Shepherds (Ashton Unity), which had an office near to the Bulls Head. Gosden's book10 gives a much fuller account of the history and great value of the Friendly Societies.

The Working Mens' Club

The miners had a club supported by contributions taken from their wages and probably referred to by Lord Vernon in 1875. Certainly in the wages sheet by the 1880s, deductions were being made, and these funds were used in loans to the union at times of strikes as we have seen, but little is known until in September 1920 the Poynton Working Mens' Club was opened on the former Rifle Club site at Poynton Green, in a building specially erected by means of a fund which had originally been started by a legacy in 1885 by Fanny Lawrance to the 7th Lord Vernon for the foundation of a village club for the benefit of workmen in and around the collieries. After an abortive plan for miners' baths had foundered because of lack of money, the trustees, which included the 9th Lord Vernon, used the fund, which with interest now amounted to £903, for this purpose. Lord Vernon added £206, with a further £1000 guaranteed for future development, but withdrew from his position as Estate Trustee and in his place two cooperative trustees, appointed by the workmen, James Wild and Thomas Ridgway were added in a new constitution to the representative trustees, Thomas Henry Hallworth and George William Clayton. The club was registered under the Friendly Societies Act.

The Club's activities were mainly recreational and social though it supported good causes e.g. a treat to children in Poynton Park in 1920, support for a floral and horticultural show by members in 1922, which continued with prizes such as the Garnett Challenge Cup being made available and help for the boy's club which it sponsored from the 1920s, with small premises in Park Lane. An early activity was billiards; the Club's team soon arranged fixtures with neighbouring clubs e.g. the Conservative Club in Hazel Grove, after G.H. Greenwell, its Vice President, had beaten R.M. Percy at an inaugural game on the new table in April 1921. Later teams played in the Alderley and Wilmslow League. The Club had a licence and drinking was an important activity despite the resistance of the United Methodists and the Temperance Movement. In 1929 some excesses had crept in for the Club was raided by the police. The Steward and Secretary were fined and the Club was struck off the register for six months. Annual outings were arranged.

In 1934 a fine bowling green was laid out on the 3½ additional acres purchased, to add opportunity for a game already very popular in connection with the Cricket Club. A cricket team was also fielded, which in 1935 at the Bollington Knockout Competition, beat Macclesfield Co-op in the final. A further very large expansion took place in 1970, for a Club which then had 721 male and 382 female members, and in 1981 further extensions were opened and the former Handicraft School was taken over.

The Co-operative Society

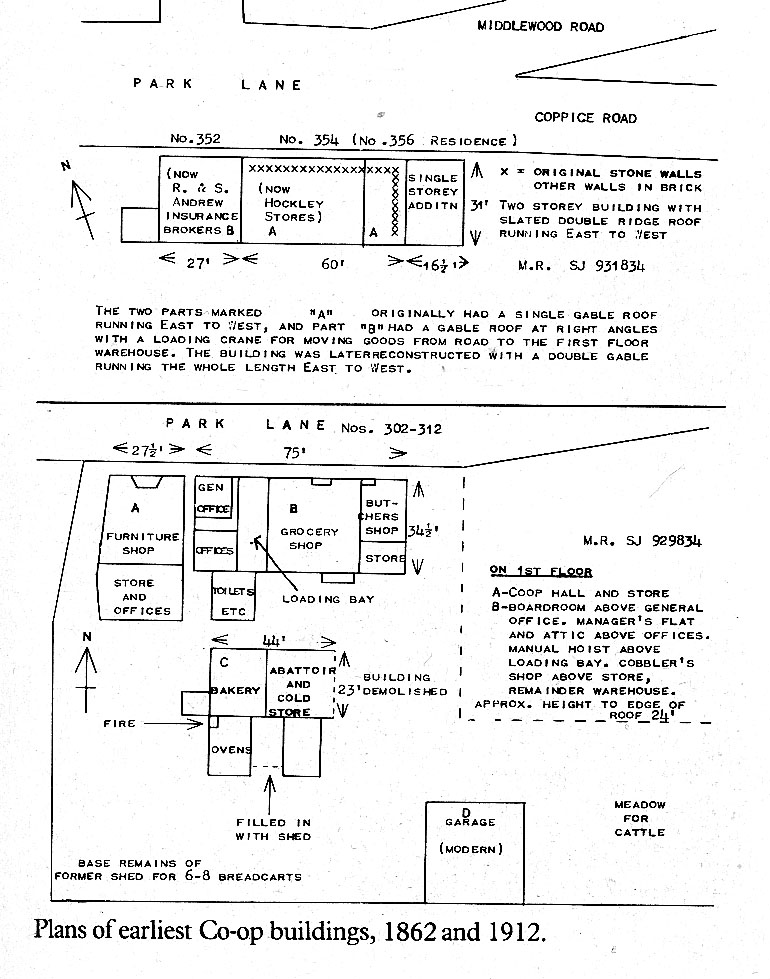

Under the Industrial and Provident Societies Act of 1852, co-operative societies were reorganised as a legal form of friendly society concerned with trading. In Poynton by 1861 there was a co-operative store described as a benefit society in the census with H.B. Elcock as manager. In 1862 this small trading association was re-founded as the Poynton and Worth Industrial Co-operative Society. This occupied the stone part of the building now known as Hockley Stores, at the top of Park Lane, either taking over and adapting an existing building or causing one to be built. The retail shop was on the ground floor and there was a warehouse above serviced by an external beam and hoist. The plans of the various co-op buildings give details. The site was chosen no doubt because of the high concentration of miners at Hockley. In 1875 the second larger building became necessary as the Society expanded. A very interesting membership book11 has survived, which shows members paying for at least two £1 shares in instalments of not less than 6d per week. Each year from 1869 to 1898 an average of 18 new members joined of many different occupations but predominantly colliers, labourers and engineers - only one farmer among the first hundred members. The new building was the one in middle Park Lane which closed in 1981, marked A on the second plan. Lord Vernon praised the enterprise but prophetically felt it was wrongly sited. The plan shows the various parts of the shop and offices on the ground floor with the warehouses on the first floor and a boardroom above the general office. A manual hoist operated through trapdoors from a loading bay below. In 1890 the Society had 232 members, in 1908 475. Business was increasing and in 1912 a new building, B on the plan, was added, by Clayton Brothers of Poynton, and the other building was refronted in Accrington brick, including a large inscription and a clock tower, (the clock is now in the Poynton Industrial Archaeology Collection). In 1890, in one quarter, relative sales were, of groceries £1819, drapery £303, butchery £542, totalling £2164 altogether. By 1913 after the new buildings had come into use, total annual sales were worth £11,791. The co-op slaughtered its own animals, which grazed after purchase in a field behind, in its own abattoir on the premises at the rear of the shop, and baked its own bread, distributed by its own vans, in a bakehouse also at the rear. Milk was also taken round for sale. The first branch was opened in Park Lane near Poynton Place in the early 1920s, and first a hut then a small shop was erected near the new council houses in Coppice Road about 1924. Middle Park Lane building was demolished in 1984.

Members could accumulate money in a share account which produced interest, had full voting rights and were entitled to a full dividend on purchases (later trading stamps). Some help was given with mortgages and the co-op built some houses for letting in Park Lane. The Society also on occasion helped the Miners' Union and the Accident Society. Cordial relations were maintained with the Co-operative Wholesale Society in Manchester, which was a vast enterprise, well described in Redfern's book.12 Members felt they were part of a great movement bringing benefits for working people. The hall was used for regular entertainments and dances. The Society was served by able Presidents and managers.

In the 1910s and 20s shop hours were long, 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. and Saturday until 4 p.m. They had decreased by 1935 because of government restrictions. Besides the direct sales there were arrangements for shoe repairs, carried out by a cobbler who had his shop on the first floor, and men's and ladies' garments could be made to measure. Members could be given a permit to buy furniture at C.W.S. headquarters, which also supplied most of the groceries. Chutes sent down flour, potatoes and mixed corn for bagging and sale. Dividends in the £ varied from 3s 10d in 1887 to 1s 3d in 1920 after the war, is 3d in 1922 and 2s 7d in 1935. By the last quarter of 1937 the branches were catching up with the central stores in sales - Central Grocery ( 304 Park Lane) £3677, Drapery £1548, Confectionery £667, Butchery £827 - No, 1 Branch (12 Park Lane) £3130 plus £653 Drapery - No. 2 Branch (at Hockley) £1757; Coal £1057; Milk £47. Despite a setback immediately after the First World War, the Poynton and Worth Society remained a successful small independent society, and played a very useful part in meeting the needs of a greatly increased population after the Second World War.

References

1. Challinor, R. and Ripley, B. The Miners' Association, a trade union in

the age of the Chartists. Lawrence and Wishart, 1968.

2. Ashworth, Thomas. Commemorative address and signatures on the occasion

of his retirement in 1858. MS in Stockport Reference Library.

3. Poynton Miners' Association, MS Accounts 1904-22 and Anson Pit

Contributors' Book 1914-21. Formerly in the possession of D.A. Kitching, now

in the Cheshire Record Office.

4. Poynton and Worth Colliers' Accident Society, MS daybooks and accounts

1890-1920. Formerly in the possession of D.A Kitching, now in the Cheshire

Record Office.

5. Ashworth, James. Ashworth's patent Hepplewhite Gray safety lamp,

Manchester Geological and Mining Society Transactions, 1887/8 pp.

550-3.

6. Royal Commission on Coal. Vol. 1. pp. 335-343. HMSO 1871 - Evidence

given by G.C. Greenwell,

7. Macclesfield Rural District Council, Poynton Sewerage Committee,

1898-1901. LRM 2472/23, CRO.

8. Scott James, R.A. Housing conditions in mining areas. Appendix to

Coal and Power, an enquiry presided over by D. Lloyd George. HMSO, 1924,

9. Manchester Unity of Oddfellows. Oddfellows Magazine from 1828

Manchester Reference Library, and General Rules 1879, Special Rules 1928 and

minute books from 1913 in the possession of the Lodge Secretary.

10. Gosden, P.H.J.H. Self help voluntary associations in the nineteenth

century. Batsford, 1973.

11. Poynton and Worth Industrial Co-operative Society. Membership Book

1862-1922. Formerly in the possession of D.A. Kitching, now in the Cheshire

Record Office. Balance Sheets, 1923-1961, In the possession of A. Walker.

See also PLHSN No. 9.

12. Redfern, P. The new history of the C.W.S. Dent, 2nd ed., 1938.

This text taken from: Poynton A Coalmining Village; social history,

transport and industry 1700 - 1939, by W.H.Shercliff, D.A.Kitching and

J.M.Ryan, published by W.H.Shercliff, 1983. ISBN 0 9508761 0 0

Chapter 10. Economic aspects of the Collieries

Chapter 12. Social life and welfare of the community

Poynton A Coalmining Village Contents

© W.H. Shercliff, D.A. Kitching & J.M. Ryan 2002

Last updated 2.4.2012